Never waste a crisis

What is a recession?

There is no single definition of recession, though different descriptions of recession have common features involving economic output and labour market outcomes.

The most common definition of recession used in the media is a ‘technical recession’ in which there have been two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth in real GDP.

Recessions are often characterised by growing unemployment and bankruptcies, as demand slows from businesses and consumers.

Whilst recessions are costly, they are argued to be the natural balancing act needed to end misallocation of investment capital when bubbles occur.

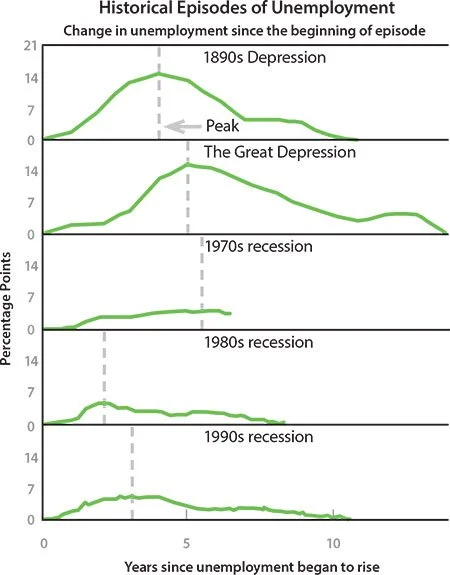

When Have Recessions or Depressions Occurred in Australia?

There are several episodes of very weak economic activity in Australia that are recognised as recessions or depressions by most economists. There are also some episodes of weak economic activity where there is disagreement among economists about whether these were recessions, in part because of the different definitions of recession that can be used.

Recessions

1974–1975:

The mid-1970s recession followed a global oil price shock in which the world price of oil roughly quadrupled. The increase in world oil prices generated high rates of inflation which were made worse by domestic wage pressures. Significant increases in the costs of production, combined with reduced demand by other economies that were in recession, caused output to contract and reduced Australian firms' ability to employ workers. The unemployment rate rose sharply from very low levels. Despite falling output and rising unemployment, high rates of inflation persisted – a situation called ‘stagflation’. (The unemployment rate peaked at 5½ per cent while inflation peaked at 18 per cent.)

1982–1983:

Around the world, the high rates of inflation that emerged during the 1970s had become entrenched, with the inflationary effects of higher oil prices reinforced by excessive growth of the money supply and expansionary fiscal policies. Given the costs of high inflation, in the early 1980s, central banks sought to reduce inflation through tighter monetary policy that resulted in recession in a number of economies (especially the United States). In Australia, the effects of tighter monetary policy and weak global demand were compounded by drought. With the breaking of the drought, a rapid economic recovery followed, aided by the benefits of the recent floating of the Australian dollar and other economic reforms. (The unemployment rate peaked at 10½ per cent).

1991–1992:

The early 1990s recession mainly resulted from Australia's efforts to address excess domestic demand, curb speculative behaviour in commercial property markets and reduce inflation. Interest rates were increased to a very high level because the transmission of tighter monetary policy took longer than expected to put downward pressure on demand and inflation. At the same time, countries in other parts of the word, in particular the United States, also entered recession, compounding the effect of tighter monetary policy in Australia. (The unemployment rate peaked at just over 11 per cent.)

Our current situation is very different to 2008, which was caused by lending excesses in the US housing market or the pandemic related collapse of 2020.

Today we need to grapple with many more factors at play which could cause a recession, such as:

• The continued impacts of the pandemic on demand (China is still enacting a COVID zero policy) and supply chains;

• The Ukraine War and global political unrest; and

• The soaring cost of energy and food..

Combined with loose monetary and fiscal policy this has caused both demand driven inflation and supply-driven inflation, which will be harder to contain with interest rate rises and quantitative tightening.

With inflation already eating into the consumer’s hip pocket the possibility of mortgage rates doubling (or more) could only further negatively impact discretionary spending. A similar story applies to a reduction in available credit.

Deflating asset prices, especially in the technology and cryptocurrency sectors, are adding to the pain.

Many retail investors entered the market only in the last few years and are now nursing heavy losses. Because these sectors include many unprofitable businesses that will now find it tough to raise further capital, layoffs are rising fast with many bankruptcies likely to follow. Even profitable businesses are now more focussed on cost optimisation, leading to efficient allocation of capital.

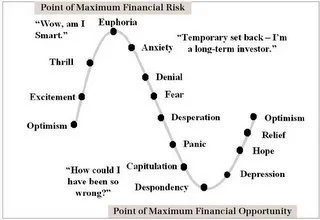

With negative sentiment and asset prices falling, intense emotions often impair rational decision-making. The below is a commonly used market psychology cycle that seeks to explain how emotions evolve and the effect they have on our investing decisions.

It's important to understand that the most opportune time to invest for the long term is when it feels the most uncomfortable, that is when the rest of the market is experiencing fear, desperation, panic and capitulation.

It’s a fool’s game to try and time the bottom.

It has been 13 years since the last real bear market (April 2020 didn’t last long enough), so it may be wise to take advantage of this one while it lasts.

Sources:

https://www.aura.co

https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/recession.html